TextaQueen in conversation with Dr Ruth DeSouza.

TextaQueen is an artist of Catholic Goan heritage, born and raised in Australia. She draws using textas (felt-tip markers) to interrogate the politics of race, gender, sexuality, and identity. Beyond white-walled gallery contexts, her work has appeared as commissioned tapestries, animations, a surfboard, a colouring-in book and calendar tea-towel, album cover art, murals, tattoos, billboards, postcards, posters, zines, and pin-up playing cards. See more at textaqueen.com.

TextaQueen and I first met in 2012 at a hui (gathering) in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland), Aotearoa (New Zealand). The two-day event brought people of colour/Indigenous feminists and activists together to talk about decolonisation, feminism and anti-racism, and to examine connections between oppressions. I was drawn to Texta’s sensitive criticality and political awareness, because we have both attempted to explore in our diverse fields what it means to occupy a “position of disquiet” as migrants in white settler-nations formed on the dispossession of Indigenous people. In New Zealand, my mother formed the Goan Overseas Association (GOANZ), but Catholic Goan migrants were few in number until immigration policy changed in 1987 from source country preference (mainly European) to becoming skills-based. Texta’s parents are Goans who were born and raised in Bombay, who then migrated to Australia just after the end of the White Australia era, around 1973. Nonetheless, traces of this policy, inaugurated in 1901, remain as it made ‘whiteness’ central to the constitution of the new Australian nation. Texta was born on Noongar land in Perth and her parents were active in the Goan Overseas Association (GOA) there, which provided a relative sanctuary from hegemonic whiteness. As Ghassan Hage observes in his book White Nation (1998), Australia is imagined by both white racists and white multiculturalists as structured around a white culture controlled by them, with Aboriginal people and migrants as exotic objects. Texta still has familial ties in Goa and visited just a year ago.

For our interview in November 2017, Texta and I met at The State Library of Victoria where, as a Creative Fellow, they were using the Library's archives of political posters to inform their own poster series about the experiences of ‘marginalised artists’ in the institutional complex; Texta’s work uses circus imagery for this purpose. By coincidence, a protest against Australia’s inhumane offshore detention policy was taking place outside the library. In our interview, we talked about racism; Australian politics; what it means to be trained in whiteness; navigating between Indigenous history and white supremacy; being Goan on someone else’s land; learning anti-indigeneity through racism; problematising fashion photography and the paradox behind fragile white female bodies; the many kinds of love; how Texta’s work is read and what the future holds for the artist.

Ruth: What aspects of Goan culture do you take into your life and work?

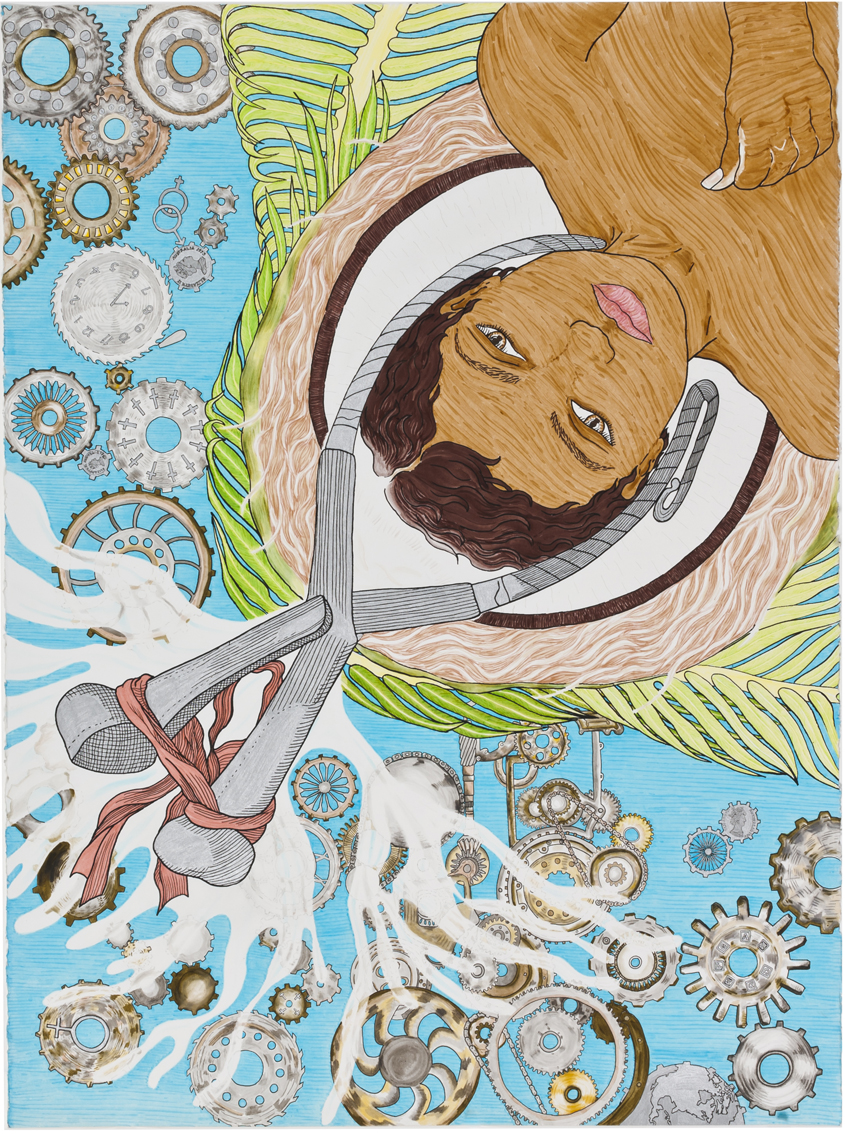

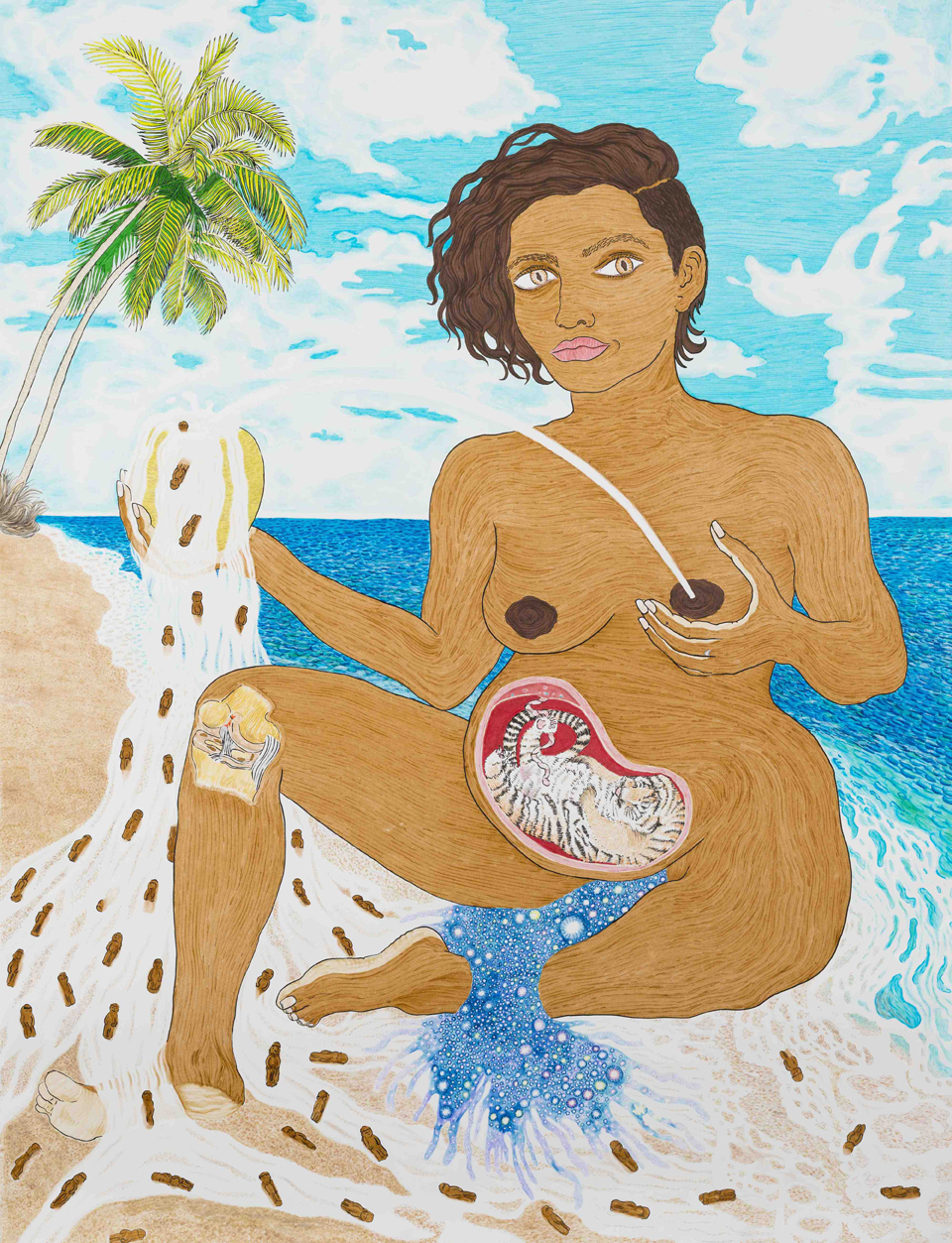

Texta: Lots of people that come to Australia or are born here have had a lot of pressure to assimilate. My 2013-2014 Coconut Legacy series, in felt-tip marker, is set in a surreal, alternate reality that's supposed to be evocative of Goa with beach and palm trees and things. In this surreal, science fictional kind of experience, I have tried to process what it means to have a specific cultural heritage that I'm so physically far away from. Both in terms of that land and being part of a diaspora. I have processed that a lot. That whole series was a fictional life narrative from conception to birth, where I was born inside a coconut as a little Chico (chocolate-flavoured and brown-coloured jelly babies sweet) baby and then the last one is me under the sand with my head out and feet out and a big tiger licking my face on the beach and that's called Reunion. It's supposed to be afterlife, the tiger symbolises some feared tentative connection with some ideas of Indian heritage.

View slideslow of Coconut Legacy series. Use arrows to navigate to the next painting.

The first related work I did was called Family Tree in 2012-2013 as part of a series called “Unknown Artist”, embodying different ideas of identity. And I thought I would do one about Goan identity. When I searched on the internet for ‘Goa’, the kind of pictures that came up were things invisibly imposed by white supremacy - tourist imagery. The picture that I ended up doing was me arm wrestling or shaking hands with an elephant's trunk.

Ruth: I love that one! I love that one so much.

Texta: Yeah, it's one of my favourite works, because I was like, "An elephant never forgets". I still embody, or my body still carries those legacies. The handshake that's also like an arm wrestle represents the complicated embrace or wrestle with identity. The palm tree in the background spills white liquid, coconut milk or whatever white liquid you might think it is, with little Chicos that represent my ancestors flowing behind and over the handshake/arm wrestle. I have used a lot of self-portraiture more recently, which makes the process of making my work really intense. All my work over time has been about how individual identity relates to collective identity. Whether it's drawing other people or myself. That's also what I'm trying to process during the self-portraits: they are of me, but I'm trying to talk about collective experiences. It makes it a very intense process to make the work, and then to show the work. Yeah.

Ruth: I bet! As you've been talking, I've been reflecting on growing up in New Zealand and how I have tried to process my Goanness through writing non-fiction, and what it means to be a Goan who lives in New Zealand and now Australia. So, I'm loving and appreciating this conversation because I've got a personal investment in your story. It's not just, “Oh, here's someone from Goa that I'm talking to.”

Texta: Yeah, it's such a rare thing to find that resonance. I think the focus of my work is trying to find that resonance with people. Most people aren't a Goan person seen as a female who's going to see the work like that. That's the beauty of making work and shows how rare it is to see an image that resonates with me and my identity on the wall, or privately that resonates with different aspects of my identity. It's so rare but such an incredible experience, and that's really what I try and do. When I get interviewed by people in the Arts Complex with whom I have little shared ground, they sometimes call my work ‘challenging’ or ask how, or why, I try to be confrontational. That’s not what that work is about. It's not about confronting. If you find it confronting, that's about you! I'm actually trying to make work to resonate with people; if someone has a poster of mine on their wall, and can see themselves in it or some tangent to themselves in it – that's who I'm making it for. Even though I'm trying to survive in capitalism, so that's probably not who is buying the original artwork, that costs more than people who live identities and experiences similar to mine can afford, because of the same systemic oppressions my work tries to critique.

Ruth: I wondered if you would say something about white supremacy in Australia because you started talking about that at the beginning?

Texta: Yeah, that's what I was talking about with the milk and being like, "What milk is it?” It's supposed to be ambiguous. Is it coconut milk? Bodily fluid? Dairy milk? An analogy to whiteness, all those things, those different legacies. There’s a reference to the Coconut Legacy, the pejorative idea of it and the heritage link. Those various invisible ambiguous liquids permeate my life in ways that I can't necessarily articulate. How white supremacy interacts with my links to cultural heritage, that is as somebody born and raised with a lot of privilege that partly comes from that ability to assimilate as a model minority person, and middle-class upbringing. I wouldn't be an artist without so many of these privileges that are also connected to my experiences of daily racism as a child. It’s taken a lot to understand how being raised in that environment, surrounded with white people, led me to receive this terrible education in whiteness, which means I can thrive in it in many ways.

Ruth: I’m thinking about these multiple identities or subject positions, which mean we can move between privilege and marginalisation depending on the context. Nothing prepared me with what I had to live with in New Zealand and now Australia. Did having a Goan community in Perth provide you with a safe space? Or a place where there were people who might understand your world?

Texta: I think it's like that pressure to assimilate. I feel like my parents didn't know what to do with what I was facing. They didn’t even tell me that they knew what was going on for me in school. I was aware they migrated and gave up a lot for the hope for a better life for themselves and their kids. They did gain a lot of privilege from migrating, and migrating for a better life on someone else's land. But acknowledging that their child or children are experiencing these dynamics is not something they really wanted to do. I remember as a kid the ways that the bus driver or people at the shopping centre would treat us. I can see that so clearly as being very informed by racism but when I talked to my mum recently, she's like, “I never noticed any of that!” And I think that's part of what I mean, like the training. The trauma that happened to me gives me my perception. Increases your ability to sense things that others who haven’t experienced that trauma can’t.

Ruth: How did your awareness about colonisation and what it means to be on Aboriginal land develop?

Texta: I learnt anti-indigeneity through the racism that I experienced as a kid because I got teased by all the swear words for Indigenous people. I had no idea what the words meant but I learned that there was somebody worse off in the hierarchy. What I might have learnt now is through the generosity of intimate friendships and connections. I feel like there are a lot of people who've done a lot of labour to inform me, beyond what I have read or seen.

Ruth: So how did the collaboration come about with veteran Aboriginal activists Gary Foley and Robbie Thorpe?

Texta: I knew Gary Foley from just being around, but I asked him if he would pose as a protagonist in a post-apocalyptic movie poster, fighting the apocalypse of colonialism, and he was into it. In the ’70s he posed, maybe as a joke, with an AK47, and someone took a photo and then the ASIO [Australian Security Intelligence Organization] was saying there was an armed Aboriginal militia or something. So, I put him on the grounds of Old Parliament House in Canberra, a landmark for Aboriginal protest, because he was one of the people who started the Tent Embassy which was erected there in 1972 to protest against a court decision over mining operations on Aboriginal land. The idea of “Creature from the Black Platoon” in 2011 was his. Part of the reason I moved towards self-portraiture is trying to process the power dynamics in me drawing other people – the different dynamics in drawing First Nations people, and me being like this “model minority” person who benefits from their genocide. The institutions that I'm showing in are built on genocide and I wonder if it makes it more palatable having Gary Foley holding a machine gun for the fact that I'm the one who drew it, you know what I mean? All those issues are why I started doing more self-portraiture. My work is infused with sexuality and gender and nudity and things, and it's really vulnerable.

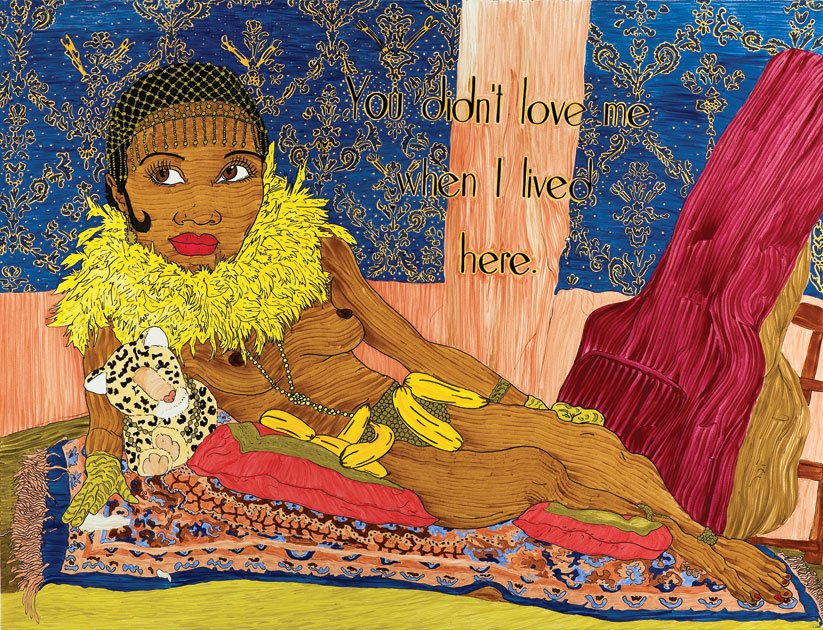

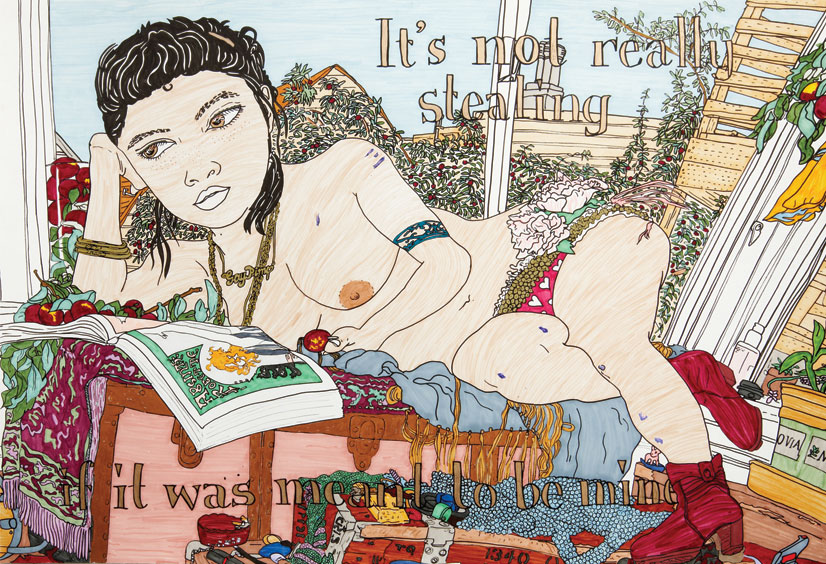

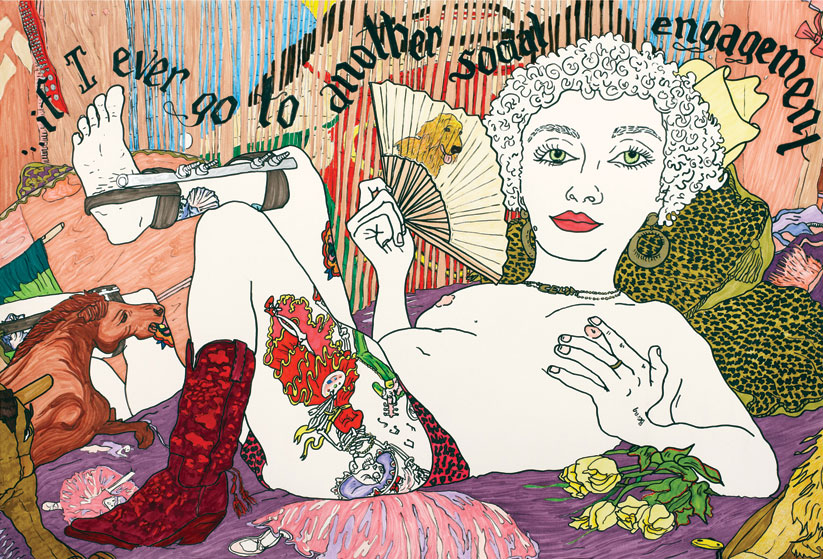

View a slideshow of TextaQueen's nudes. Use arrows to navigate to the next picture.

Ruth: Can you tell me a bit more about that? The sexuality and nudity?

Texta: That's called Save Yourself (self-love self-portrait) from 2013. It’s me holding myself [pointing to poster of work on wall]. I've been re-processing what this process is about in the wake of marriage equality, because I've felt so alienated by the whole campaign. Love is elevated, but of a certain kind, monogamous, normative love, and romantic love. It’s super alienating and hard to deal with, not because I'm a lonely single person; I'm hardly ever lonely. The really isolating thing is linked to capitalism, a love that means wanting to get all your support from one person who you prioritise. One person that you're in a romantic connection with. I couldn't survive without my support network, which in some ways is romantic but not sexual. I've been recontextualising that to think of rescuing yourself from ideas of being saved by romantic love, because that's what gets sold, and it doesn't work. Does it? I don't know. The world does reward people who stay together no matter what. And the way that the world looks on a “single woman of a certain age” as undesirable.

A lot of people in normative relationships don't get it. I see the way people in relationships are elevated and built up and connect with each other. And it's a real thing where people pity you for not having their kind of love, which most of the time you might think “hmmm … I don’t want what you have”. It’s connections with people that get me through. The hardest thing about being single isn't being lonely or being single in itself – it's fighting every day the internalised stuff and also the projections from the whole world, all the time, that romantic love will save you from any of your discontent, you know? And that's the hardest thing about it. I think. But that's also … that's something that if I was in a relationship I would be so relieved that my parents would be happy for me. You know? Ridiculous anyway.

Ruth: Can you tell me a little bit more about the work you did in Mornington Peninsula?

Texta: I did a photographic series a year and a half ago, now, while doing a two-month residency at Police Point, Boonwurrung country [South of Melbourne]. It was quite isolated. There are these big mansions right next to the place and a national park on the other side, but not that many people would go down to the ocean or walk the bush there, even though it was still warm and everything while I was there. I had a lot of time alone by the ocean. The series I did before that is linked. They were self-portraits of me that were hybrid landscapes between the landscapes I was in and Indian iconography, elephant trunks and tigers, and things like that. In the Mornington work, I'm naked and drape myself in seaweed or make the plants look like high fashion clothing. I was thinking epically in this science fiction way that I was this timeless entity that swam across from my ancestral lands in Goa and found myself there, and was trying to make sense of there. It's called Eve of Incarnation, so there's a Goan influence, some kind of Catholic-like Eve expelled from the land to this other place and trying to clothe myself. There's a lot of Catholicism running through my works. It's definitely a big influence in my life, being an ex-Catholic.

That photo series just felt really catalytic in lots of personal and creative ways. It's so layered and it's so cross-genre in that it references high fashion, and there's just so many narratives that can be drawn out of it, of the science fiction idea of me being the entity, the high fashion commentary, being a woman of colour, and the landscape. Part of it was also how do I connect to a land that I don't belong to, as a brown body in a landscape? There's so much photography of fragile white femininity, or not fragile white femininity, in a landscape that is supposedly passive. But actually, that body is there because of the violence of colonialism. How am I in that landscape, benefiting from colonialisation of this land but also here because of colonialisation of my lands? How do I process that? Then there’s the artifice of high fashion and awkwardness, awkwardness in the majesty there which is kind of me. It wouldn't have worked if I wasn't brown-skinned. It’s definitely about being brown-skinned. I was exploring how to connect to this land that's not mine. How do I be in nature? Nature is such a neutralising term, when it's a specific land of a specific people, and I'm here because of so many reasons.

It's funny how so many dudes so removed from so many things will be like: "Looks like you're having fun!" And they’ve missed the point that I'm processing all the dynamics of sexuality, gender, race, and other things in the world I experience. I'm making this work that has all this vulnerability, but which gets trivialised when it's actually so complex and layered and deep. I don't know if there's a place in contemporary art for my work. I think that's why my work can slip through sometimes, because it’s only read at a surface level. It’s bright, and poppy. I use markers, which are a kid’s thing. Yet, they are subversive ways of getting really complex things through; people can easily minimise the power of it.

Ruth: Leela Gandhi in Postcolonial Theory (1998) talks about how the colonised were always treated like children and that colonised culture was viewed as childlike or childish, which justified the logic of the colonial civilising mission as a process of bringing the colonised to maturity.

Texta: In the art world I still experience intense paternalism from white people, women often younger than me paternalising me intensely. Touching me, patting me. I'm so much more aware that I don't deserve to be treated that way. And sometimes that makes it harder to be in those circumstances in some ways.

Ruth: Is there anything that we haven't talked about that you think is important?

Texta: I'm going to show work from my last series (which is about British Colonialism in India) in London in 2019.

Dr. Ruth DeSouza originates from Bardez, North Goa, but was born in Tanzania. Her family moved to Kenya and then Aotearoa, New Zealand. She currently lives on the unceded lands of the Kulin Nation, 100 kms from Melbourne, Australia. She is a nurse, writer, researcher and academic with a passionate interest in race, gender, and issues of health. More here: ruthdesouza.com/