This review by Selma Carvalho first appeared on The Goan, 23 April, 2016.

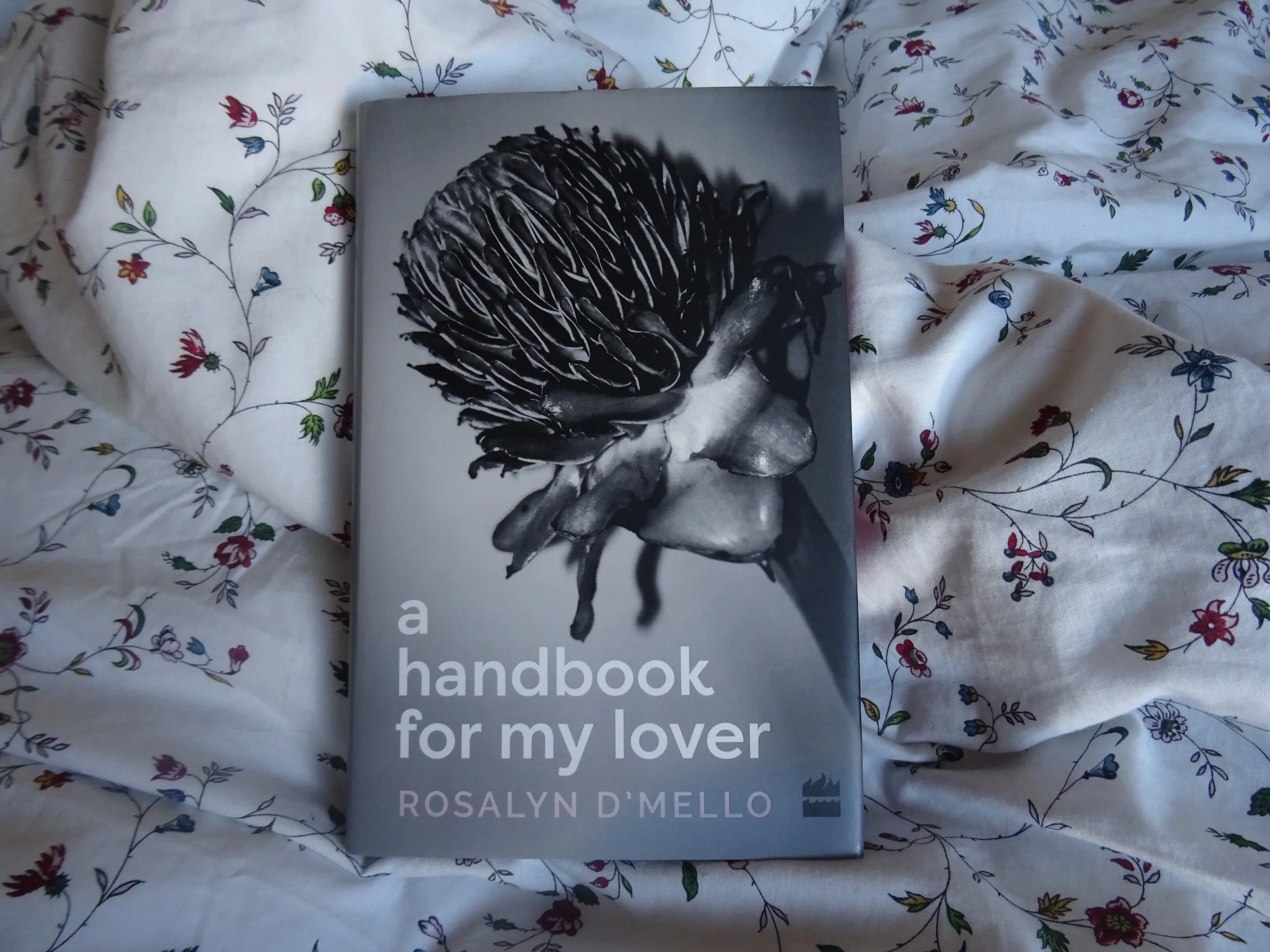

For several reasons, Rosalyn D’Mello’s book A Handbook for my Lover, should have created a bigger buzz than it did in Goa’s chatterati fora. For one thing, Rosalyn (you’ll forgive me the familiarity of using her first name, but in the interest of transparency, I’ve known Rosalyn in her cyber avatar ever since she was a literary pup, and matronly marms and conservative men were advising her against the ‘debauchery’ of her writing), is an exceptional talent; one of the most prodigious and seminal literary writers to have emerged of Goan lineage on the national and, dare I say it, soon on the international stage. Secondly, she is seriously Goan; Rosalyn talks almost brazenly about cooking sausages sautéed in red onions and weeping at cemeteries where the fund of her Goan legacy lies buried deep.

The other reason Rosalyn should find more mention by Goans, is because, like F. N. Souza who led the Indian modernist movement by stomping on our middle-class prudery, Rosalyn expands the breath of Indian erotic literature by tackling taboo subjects such as masturbation and menstruation. And she does this rather courageously, at a precarious time in our history, when the idea of womanhood and nationhood has been conflated with perverse ideas of purity.

Rosalyn’s book is part epistle and part diary. Spanning roughly six years, it traces the transformation of her relationship with the thinly-disguised P.B. Everyone who’s anyone knows exactly who P.B is. This is not a fictionalised tale of love. It is listed as non-fiction and Rosalyn has never denied that it is entirely autobiographical in nature. What elevates this from being just another love story is the exquisite prose and perfect pitch of her writing, and yes, in part, the profundity of it. As a love letter, it has all the Byronesque brooding pathos of a poem captured in the long form of prose, or rather it has the pathos of Lady Caroline Lamb, who driven to distraction by Byron eventually wilted away.

This is not a book that is going to be hailed as essential reading for radical feminists. This is not that book which furthers the cause of greater female agency. Rosalyn doesn’t sublimate work for love. Rosalyn doesn’t stop questioning what the absence of children will mean to her future (‘Sometimes I think about all our unborn children who’ve escaped through my womb because we couldn’t risk seeding them’). Rosalyn doesn’t deny she is her lover’s nursemaid and domestic helper. Rosalyn doesn’t wish away the permanence of a traditional ‘home’. Rosalyn isn’t stoic in the face of P.B’s petty cruelties. She crumbles and cries, and like a grieving Demeter wets the earth with the salt of her tears, (‘You have led me to bouts of madness in every conceivable public place. I have wept, on your account, in all forms of transport – buses, autos, planes, trains, scooters, cars – and in all habitable spaces’). It is precisely because Rosalyn is so fragile, so thwarted and so conflicted, that we can identify with her as a woman, and an honest one at that. The feminist ideal of the strong, self-sustaining woman is about as emotionally and intellectually captivating as a caged canary. In real life, people have very little agency in relationships. Like Rosalyn, they are swayed by emotion, need, lust, want and circumstance. One does not affect a desired outcome, at best, one can only craft a moment and have animal-like instincts to survive the long run.

One does wish however, that her publisher had paired her with a more conservative editor. It feels, for instance, as if the story and the couple live in a bubble of their own making reinforced by rituals of single-malt whiskeys. We don’t know anything about P.B’s past except that he was not particularly nice to women and had formerly indulged in some light domestic battery (‘If fact, in my past relationships, I have known to be physically violent’, he tells her). We don’t know if P.B had a childhood or an adolescence, or if he emerged fully formed, all brutish and bristling, (‘You are prone to sudden fits of rage when something suddenly clicks and shifts inside your brain and your mouth spews venom’). I vaguely recall having a phone conservation with said brute in London some years ago, and he was utterly charming.

In the end, Rosalyn may well be an amalgam of classic and modern romantic heroines, from Bronte’s Jane Eyre who convinces the rotten Mr Rochester of his dependence on her, to Candace Bushnell’s long-suffering Carrie Bradshaw who weathers Mr Big’s blasé attitude towards commitment, to emerge triumphant. I for one, am already keeping a vigilant eye on the release of Rosalyn’s next book.